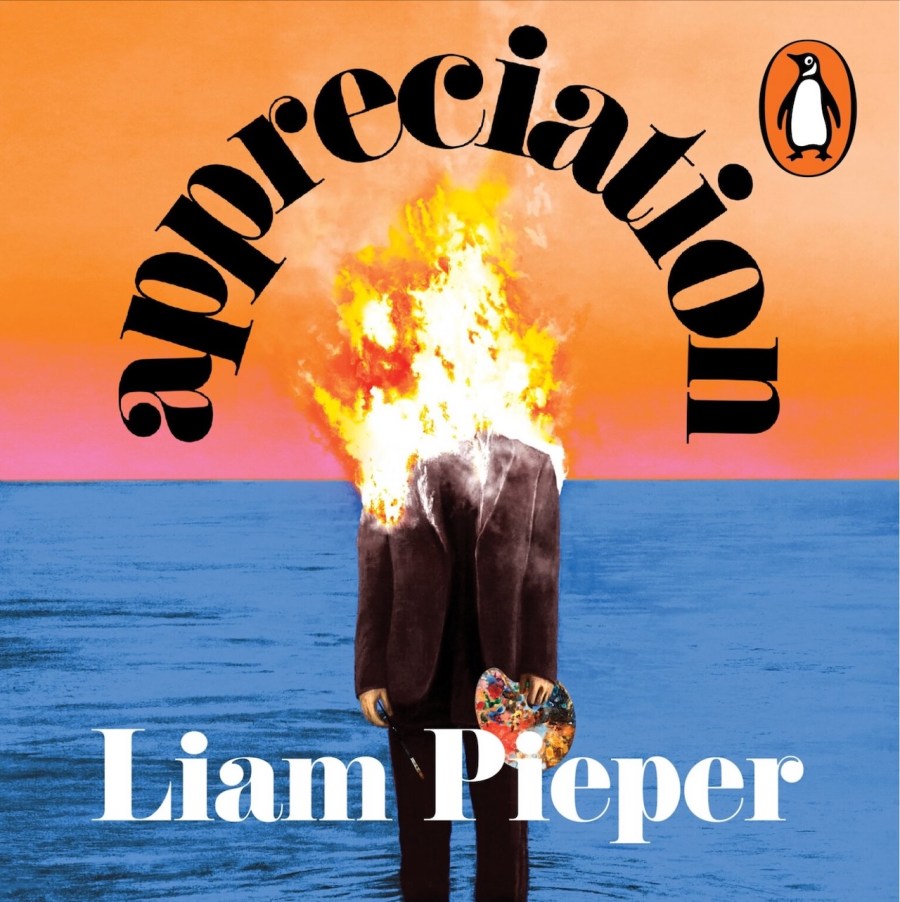

Anyone who is passionate and sincere about creating art would be familiar with the self-doubt, imposter syndrome, and rage that can creep up without warning, all consuming and tumultuous as it is channelled into creativity. Woo Woo by Ella Baxter is about a feminist performance artist questioning herself in the lead up to her latest exhibition.

I am impregnating every image with my unruly, creative juju. Are you getting my full body in? … The shoes?

It is a week before conceptual artist Sabine’s solo art exhibition, titled Fuck you, Help Me, in a Melbourne gallery. The show is comprised of fifteen photographs of the artist in costume taken outside at night. She is wearing the mask of a female archetype and a translucent body sheath.

It’s about pretending to be something you already are.

Despite being an established artist, Sabine is having a crisis of confidence. She is dealing with a real life stalker who loiters in her garden and sends her caustic letters that unsettle her. She is also being visited in her house by the ghost of 20th century feminist performance artist, Carolee Schneemann. The stalker, who Sabine calls ‘Rembrant Man’ feeds her sense of anxiety and doom, while Carolee becomes an ally and mentor.

What a thought-provoking piece Sabine provided for us this evening. Brings to mind such questions as what fear is, why we run, who the man represents, what is considered safe—an so many more! Great work tonight, Sabine! We were all right there with you! Brava! (Dare we say, encore?)

Sabine is married to an adoring husband, Constantine, who is a chef and her primary emotional support. He grounds her and placates her anxieties. He is not sure how to deal with the stalker, or even whether he believes the stalker exists. He thinks Sabine is just worked up about the exhibition, as usual. She is after all easily spooked – by the tenuousness of her place in the art world, by the number of fans that follow and join her livestreams. Her anxiety about validation leaves her vulnerable.

It was necessary for him to provide some Yang to her constant, thrumming Yin.

Suspend belief and be prepared to indulge in some visceral feral mayhem. I suspect it is one of those novels you will either love or hate, depending on your relationship to the world of art and artists.