“…our stories influence what we see and what we believe is possible or impossible in the world.” – Ethan Miller

My post last week was a response to events in Australian politics that I found exasperating. The political circus continued to get my goat so much I wrote a letter to The Age.  My week of political writing got me thinking about the role of fiction in relation to politics.

My week of political writing got me thinking about the role of fiction in relation to politics.

When we consider politics and writing we generally think of journalists. If a journalist fabricates content it is a betrayal of public trust, but making stuff up is the very purpose of creative fiction so does it have a role in politics? Is there such a thing as fiction that is not political? Is writing fiction a political act?

Many say they are not political (or not interested in politics), but the sociopolitical environment in which we reside shapes our entire lives. Politics determines the haves and have-nots. It tells us who’s experience is legitimate. For example governments determine whether  medical facilities exist to ensure we survive childbirth, dictates if we get the opportunity to learn to write at all, the price of milk, who we can and cannot love, and the type of death we can have. Our very existence is enmeshed in, and shaped by the political environment(s) we live in and are exposed to.

medical facilities exist to ensure we survive childbirth, dictates if we get the opportunity to learn to write at all, the price of milk, who we can and cannot love, and the type of death we can have. Our very existence is enmeshed in, and shaped by the political environment(s) we live in and are exposed to.

Work of the creative imagination, be it fiction, poetry, art or drama, is shaped by our own experience and our views of the world – in other words our own sociopolitical lens. The world shapes us, and then as writers we try to shape the world. We question or bend reality, invent new worlds and invite readers to consider a new perspective. To understand the other. We pick out themes and create personalities that we sew together into a plot to show, magnify or transform how a particular set of circumstances can impact on the world now, or in the future.

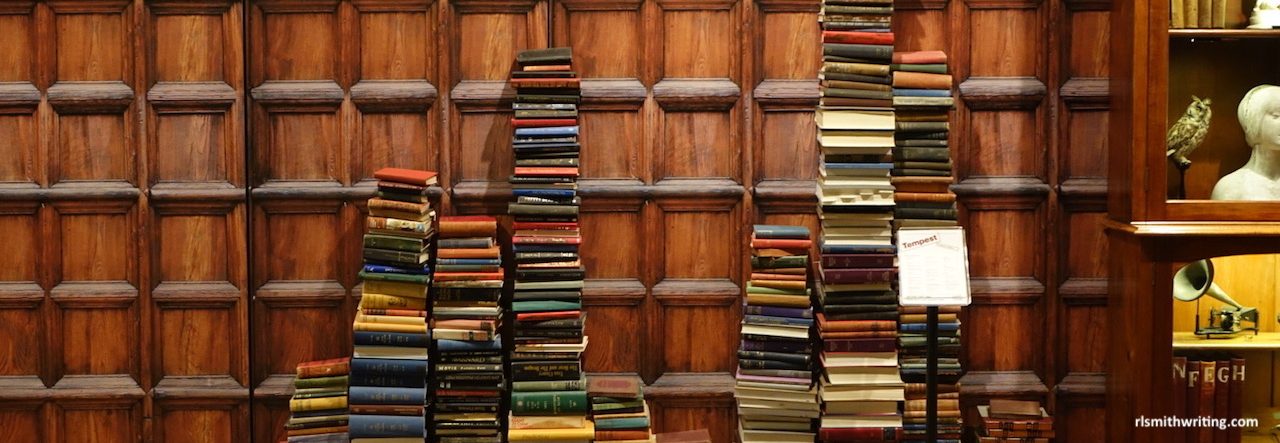

What reader would not be able to name a book that had a significant influence on their lives? Writers, story tellers and poets have been holding a mirror up to reality for centuries. They often say what would otherwise be considered unsay-able in public.

The threat writers pose is evident when we study the history of censured, banned or  burned books. Examples of fiction works that have been subject to some kind of censorship or ban at one time or another include Dr Seuss, Winnie the Pooh, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Catch-22, The Da Vinci Code, Doctor Zhivago, Nineteen Eighty-Four, The Satanic Verses, Sophie’s Choice, The Well of Loneliness and Ulysses. The more restrictive a political regime, the more likely it is to see text as a threat. Over 25,000 books were burnt in Munich four months into Hitler’s regime for being ‘unGerman’.

burned books. Examples of fiction works that have been subject to some kind of censorship or ban at one time or another include Dr Seuss, Winnie the Pooh, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Catch-22, The Da Vinci Code, Doctor Zhivago, Nineteen Eighty-Four, The Satanic Verses, Sophie’s Choice, The Well of Loneliness and Ulysses. The more restrictive a political regime, the more likely it is to see text as a threat. Over 25,000 books were burnt in Munich four months into Hitler’s regime for being ‘unGerman’.

A lesser known but poignant example of how literature can threaten and intersect with politics was a book called New Portuguese Letters (Novas Cartas Portuguesas) by Muria Isabel Barreno, Muria Teresa Horta and Maria Vento da Costa. The book, published in 1972, was a post-modern collage of fiction, personal letters, poetry, and erotica inspired by the original letters of a Portuguese nun, Mariana Alcoforado to her lover, the Chevalier de Chailly, at the time of Portugal’s struggle for independence against Spain. When New Portuguese Letters was written the Portuguese had been living under a dictatorship for almost fifty years and the book exposed the tyrannical relations that existed between the sexes.

The authorities banned New Portuguese Letters soon after its release – though not before a copy was smuggled to French feminists in Paris who arranged for its translation. The three Marias were arrested and allegedly tortured by the regimes secret police. They were charged with ‘abuse of the freedom of the press’ and ‘outrage to public decency’ by a censorship committee. The three women were criticized because they wrote like men. They were sexually explicit, frank about their desires, fantasies, sexuality and bodies. They critiqued patriarchal structures, family violence and political repression.

The trial dragged on for two years, made worldwide headlines and gave rise to protests  outside Portuguese embassies in Europe, the United States and Brazil. On 25 April 1974 a bloodless coup overthrew the regime. It was called the Carnation Revolution because red carnations were put in the ends of soldiers’ gun barrels. Soon after the coup the case against the three Marias was dismissed, the women freed and the book became a literary symbol of women’s liberation, erotic art, and the Portuguese revolution.

outside Portuguese embassies in Europe, the United States and Brazil. On 25 April 1974 a bloodless coup overthrew the regime. It was called the Carnation Revolution because red carnations were put in the ends of soldiers’ gun barrels. Soon after the coup the case against the three Marias was dismissed, the women freed and the book became a literary symbol of women’s liberation, erotic art, and the Portuguese revolution.

At its essence politics is about power and the rules we impose on society as a way of maintaining order. Do all authors strive to effect change in the world through their writing? If we don’t, why do we hope to be published and read?

What about genre fiction? Is romance gender politics at work? The genre is often dismissed as unworthy. Is that not itself political? Is to disregard romance a dismissal of women (the main consumers of romance), their views on relationships and their sexuality?

Is mystery fiction social justice at work? It often explores and gives voice to the fringes of society – drugs, prostitution, the dispossessed, or the underdog taking on the powerful elite. The very essence of a mystery is about who holds power, who abuses power and how the imbalance can be redressed. That is political. Mystery authors often use their writing to bring to light the concerns of minority groups and to provide commentary on a societies moral issues – Val McDermid’s lesbian protagonist, Lindsay Gordon; Emma Viskic’s deaf character, Caleb; Barry Maitland’s Aboriginal protagonist in the Belltree trilogy.

Reading a novel uncouples us from our ordinary lives and transports us to a self-created world through our interaction with a work of fiction. We read fiction to get ‘lost in a book’ or to ‘escape from our own existence’. Reading is an opportunity for some kind of small transformation.

Writing is a way to contribute to the development of a liberal and democratic society. We implant meaning and messages in our plots that we hope will influence how our readers think, not only entertain them.

Writing is a way to contribute to the development of a liberal and democratic society. We implant meaning and messages in our plots that we hope will influence how our readers think, not only entertain them.

We judge and unpack what we read and ascribe a value to books. That is political – just read any book review or go to a book club meeting and listen to the debate about a novel to see how a single story can take on different contours and unique significance for individual readers.

How do you hope to influence your readers?

Main image: DOX Centre for Contemporary Art, Prague;

Inset images in order: Letter to The Age; Street Art, San Francisco; Guggenheim museum, New York City; Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane; Threat and Sanctuary, Museum of Modern Art, New York City

be holed up with friends in a beautiful spot near Byron Bay on the north coast of New South Wales. Our days are made up of surfing, eating, whale and dolphin watching, reading and writing. Oh, and there’s the spectacular sunrises and sunsets that occur at this most easterly point of Australia.

be holed up with friends in a beautiful spot near Byron Bay on the north coast of New South Wales. Our days are made up of surfing, eating, whale and dolphin watching, reading and writing. Oh, and there’s the spectacular sunrises and sunsets that occur at this most easterly point of Australia. Sadly, the enhanced attention to detail doesn’t prevent me from missing errors when proof reading my own work. A couple of friends staying with us asked if they could read some of my book. I had edited and edited, and edited the first three chapters, which I entered into the Richell Prize and The Next Chapter in July, so sent them those parts to read. Their feedback was positive and one of my friends did a great job picking up some grammatical errors I had missed. It did make me realize just how invisible your own writing becomes when you have been absorbed in it for months and months.

Sadly, the enhanced attention to detail doesn’t prevent me from missing errors when proof reading my own work. A couple of friends staying with us asked if they could read some of my book. I had edited and edited, and edited the first three chapters, which I entered into the Richell Prize and The Next Chapter in July, so sent them those parts to read. Their feedback was positive and one of my friends did a great job picking up some grammatical errors I had missed. It did make me realize just how invisible your own writing becomes when you have been absorbed in it for months and months.

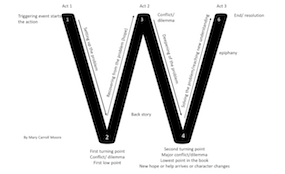

basic structural elements of a story as without it your story is likely to flop soon after take-off or require endless re-writing to turn it into something that will engage readers.

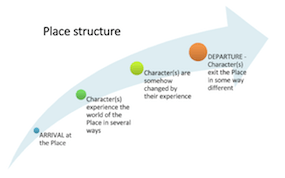

basic structural elements of a story as without it your story is likely to flop soon after take-off or require endless re-writing to turn it into something that will engage readers. points that each align with an archetype.

points that each align with an archetype. when they leave.

when they leave.

tribulations and adventures of a sleek black horse. Black Beauty highlighted the issue of animal welfare and the importance of treating others with kindness, respect and sympathy. Important lessons for any child. Roald Dahl bought garden bugs to life in his 1961 novel James and the Giant Peach that explored the themes of friendship, death, hope, fear, abandonment, rebellion and transformation. I remember being fascinated by the giant caterpillar who had to tie the shoe laces on his many pairs of boots every morning. The book is still on my shelves and I pull it out and re-read it every now and then.

tribulations and adventures of a sleek black horse. Black Beauty highlighted the issue of animal welfare and the importance of treating others with kindness, respect and sympathy. Important lessons for any child. Roald Dahl bought garden bugs to life in his 1961 novel James and the Giant Peach that explored the themes of friendship, death, hope, fear, abandonment, rebellion and transformation. I remember being fascinated by the giant caterpillar who had to tie the shoe laces on his many pairs of boots every morning. The book is still on my shelves and I pull it out and re-read it every now and then. allegory of the Manor Farm ruled by pigs. As power goes to their heads the pigs start to run the place on the premise that “All animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others.” They become so much like the humans they overthrew that eventually they transform into humans themselves.

allegory of the Manor Farm ruled by pigs. As power goes to their heads the pigs start to run the place on the premise that “All animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others.” They become so much like the humans they overthrew that eventually they transform into humans themselves. fair to stay things were going swimmingly. I had established a great routine of writing early, doing some exercise then either writing again, reading or heading out into the garden depending on the weather. Then along came Harper.

fair to stay things were going swimmingly. I had established a great routine of writing early, doing some exercise then either writing again, reading or heading out into the garden depending on the weather. Then along came Harper. Many country dogs get adopted in Melbourne, and Seymour is a liaison point apparently. The industry is quite mysterious and I think there could be a great fiction story written about the rescue, movement and adoption of animals.

Many country dogs get adopted in Melbourne, and Seymour is a liaison point apparently. The industry is quite mysterious and I think there could be a great fiction story written about the rescue, movement and adoption of animals. Staghound-kelpie cross at home. “Best dog he’d ever had,” he said, “affectionate, trainable and not as energetic as a kelpie. Likes to lie around on the couch and watch TV.” Sounded like an ideal writing companion.

Staghound-kelpie cross at home. “Best dog he’d ever had,” he said, “affectionate, trainable and not as energetic as a kelpie. Likes to lie around on the couch and watch TV.” Sounded like an ideal writing companion. people who dropped by and Bunning’s. Believe it or not Bunning’s has a very detailed dog positive policy and we were able to take Harper around the store introducing her to the weird and wonderful world of the great Aussie tradition of a trip to the hardware store.

people who dropped by and Bunning’s. Believe it or not Bunning’s has a very detailed dog positive policy and we were able to take Harper around the store introducing her to the weird and wonderful world of the great Aussie tradition of a trip to the hardware store.