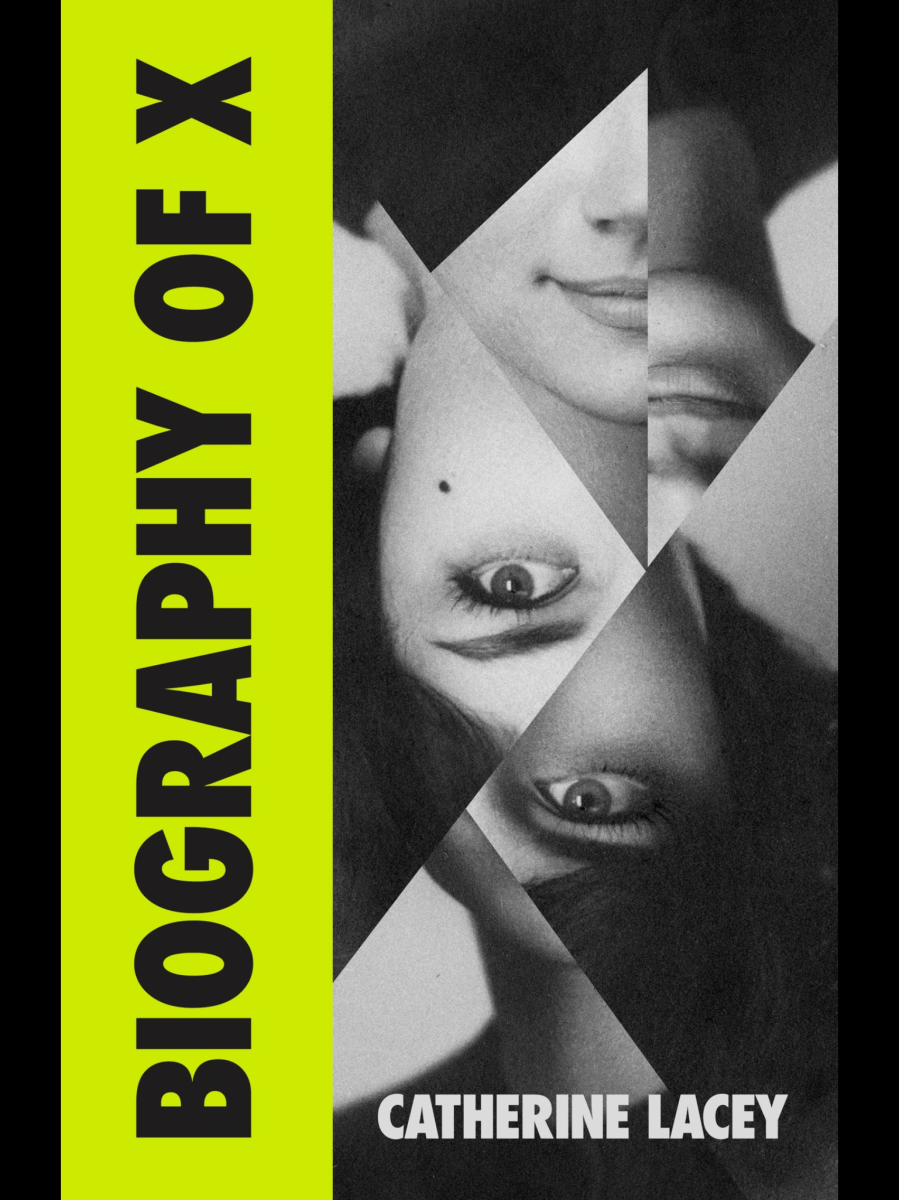

The title of this book—as titles so often are—is a lie.

Biography of X by Catherine Lacey is an odd, but compelling genre-bending work of fiction. It is written in the style of a biography, including photographs, bibliography and references with footnotes, by a narrator who is a journalist. Biography of X is set in a USA with an alternative history in which the southern states have succeeded during the ‘great disunion’ of 1945 and become a dictatorial theocracy.

The sky was moonless and blasted full of stars, and as I looked at them, exhausted into naïveté, I felt almost fearful of the vastness above me.

X was an eclectic artist, of books, music and art installations. Before her death in 1996, the mysterious X had collaborated with the likes of David Bowie and Tom Waits. She took the name X in 1982. It was unclear whether any of her many prior pseudonyms where her real name.

The first winter she was dead it seemed every day for months on end was damp and bright—it had always just rained, but I could never remember the rain—and I took the train down to the city a few days a week, searching (it seemed) for a building I might enter and fall from, a task about which I could never quite determine my own sincerity, as it seemed to me the seriousness of anyone looking for such a thing could not be understood until a body needed to be scraped from the sidewalk.

The narrator/author of the biography is, CM Luca, X’s widow. She is obsessed with trying to find the truth about the woman to whom she was married. She is motivated to write the biography after becoming infuriated by another published by someone else that she feels misrepresents her beloved.

This pathetic boy—no biographer, not even a writer—was simply one of X’s deranged fans. I don’t know why she attracted so many mad people, but she did, all the time: stalkers, obsessives, people who fainted at the sight of her. A skilled plagiarist had merely recognized a good opportunity and taken it, as people besotted with such delusion hold their wallets loosely.

Despite their marriage, when X died, Luca did not know her birthplace, date or real name. She sets out to piece together X’s past, untangle fact from fiction and process her own grief through a series of interviews with former spouses, lovers, and friends. Luca trawls through papers left behind by X trying to make sense of who her wife was and by extension their relationship and herself.

We cannot see the full and terrible truth of anyone with whom we closely live. Everything blurs when held too near.

X was clearly brilliant, difficult and troubled in the way that great artist often are. Her relationship with Luca was imbalanced and dysfunctional. Luca traces X’s origins to the Southern Territories and seeks out her family of origin, her roots as a revolutionary or terrorist depending on whom she speaks to.

But I did not find this so awful. Grief has a warring logic; it always wants something impossible, something worse and something better.

Biography of X is one of the most unusual and ambitious works of fiction I have read in a long time. Its mesh of genres, bending of history, and melding of the real with the imagined is discombobulating and enthralling.

Perhaps your ability to feel it waned, perhaps you are the one who ruins things, it was you, you—and there it was again, that useless, human blame two people will toss between each other when they become too tired or weak to carry the weight of love.

There was so much in this novel, both in form, content and emotion that it took me a long time to read it, but I am glad I did.