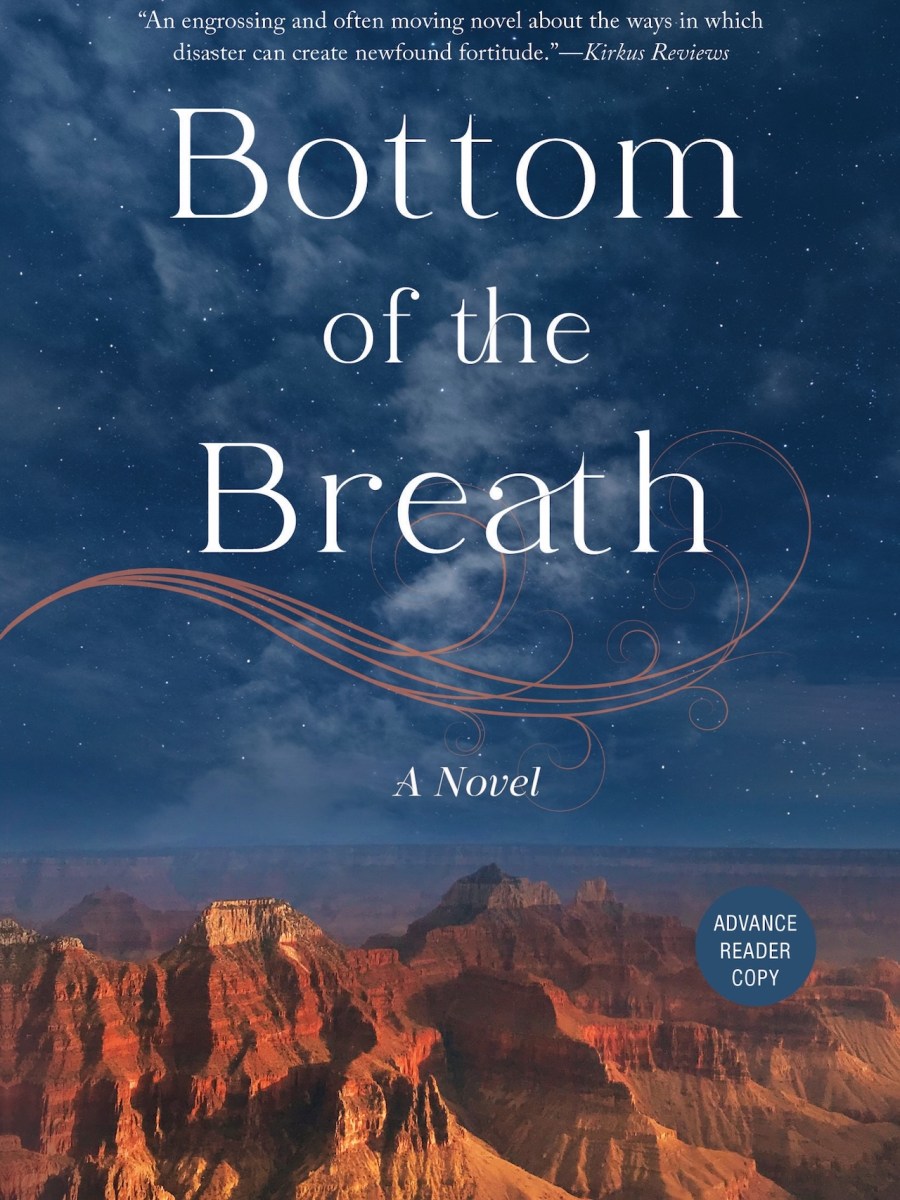

Debut novel Bottom of the Breath by American author Jayne Mills is intriguing from the opening. It is a story about a woman called Cyd coming to terms with revelatory family secrets after receiving a surprise inheritance, overcoming betrayal, and facing her fears to discover that she is much stronger than she believed herself to be.

Helen’s recipe for a happy life, then and now: Stop wanting something other than what is.

There is a massive storm heading straight for the small coastal town of Lola in Florida and the residents are battening down the hatches in preparation. The approaching hurricane provides an ominous backdrop and sense of foreboding to the beginning of Cyd’s story and is a great vehicle to amplify the tensions emerging in her life. Cyd is helping her friends Helen and Nick for prepare the Osprey Cafe for the onslaught of the storm.

I’ve lost my ability to imagine what I should do or can do. I need something or someone to believe in.

Nick asks Cyd to drive to a nearby town to pick up some supplies for the café and she agrees despite an aversion to driving. Noticing patterns in the everyday, Cyd experiences a surge of happiness when she glances at the car’s clock and sees the time 11:11 right before a cataclysmic event. When Cyd discovers the circumstances of what happened to her it disrupts her life and her sense of self, and a transformative journey begins.

There is no beginning and no end, just layer upon layer of rock and sediment for as far as she can see, dug through to expose the very heart of the earth. The colors are endless, at once muted and brilliant: purples and blues, oranges and golds, deep green and stark white. There are cliffs and gullies, mesas and buttes, and sandstone walls penetrating a vertical mile from top to bottom.

Travelling from Florida to Sedona and the Grand Canyon in Arizona, Cyd goes in search of answers, and in search of self. I remember visiting the Grand Canyon back in 2005 and being in awe of its vastness and Mills does a great job of capturing that sense. The Grand Canyon scenes are another example of environment as character in the story and how nature can shape us. I particularly enjoyed this element of Bottom of the Breath.

It represents beginnings and endings, the natural passage of the cycles of life. The perfection of the path that has led her to this moment is as clear as the stream she waded in the previous day. There is no room for regret. Regret is wasted energy. None of her past can be changed nor should it be. Only her mindset can change. The story can change.

Bottom of the Breath is contemporary fiction with elements of adventure, mystery and romance. Discover a new literary voice by pre-ordering Bottom of the Breath now from your preferred bookstore or it will be available for general released on July 8, 2025, published by She Writes Press. Thanks to Jayne Mills and She Writes Press for the ARC.

While I was reading Bottom of the Breath some questions came to mind that I wanted to ask Jayne and she was kind enough to take the time to respond:

What inspired you to write this particular book? I’ve heard it said that oftentimes the book you set out to write is not the book you actually write. That was true for me. The first germ of an idea was one I carried around for decades. It is based on a true family secret. After the shock of what I learned wore off a bit, I thought, “This would make a great book.” Much of the story changed as I wrote, but that part never did.

What was most challenging in the writing of the book? You don’t know what you don’t know. Although I have always been a voracious reader, it wasn’t until I wrote the first draft of this book that I realized how little I knew about structuring a novel. I had to study the craft over the course of years as I wrote. I also had to write as much as I could while working full-time in my “real” job as a portfolio manager. I would tell any writer, don’t doubt that you can write a book in 15-minute intervals. You absolutely can!

What’s your favorite part of the writing process? I love writing. It’s my meditation. I truly never tire of it.

Do you have a specific writing routine or environment? I wrote this book whenever I could, mostly early mornings and weekends. But I will write whenever and wherever. I don’t have a particular routine as far as a place or a word-count goal. My life is too varied for that type of structure. I am a disciplined and determined person, though, so that helped me stay committed over a long period of time.

What are you working on now? I’m working on my second novel, which is set in my hometown of St. Augustine, Florida, the nation’s oldest city. I love setting. It plays a huge role in Bottom of the Breath, and it will play a big role in my next book. St. Augustine is steeped in history and is known for its ghost stories. The town and some of its past residents will be part of my next literary adventure. I’ve also gone deep down into the astrology rabbit hole over the past couple of years. It’s my latest obsession, and I’m studying every chance I get.

What authors inspire you? So, so many. I love everything by Liane Moriarty and Ann Patchett. Lauren Groff and Maria Semple are incredible. I just discovered Eleanor Lipman, who is delightful, and I recently devoured Bear by Julia Phillips. Alice Munro and Claire Keegan are among my favorite short story writers. I just reread Jane Eyre. (It was my mother’s favorite.) And I’m reading Constance Fenimore Woolson, who wrote in St. Augustine in the late 1800s as part of the research for my next novel. (Yes, I read men, too! I thoroughly enjoyed Who is Rich by Matthew Klam, and I could read Breakfast at Tiffany’s every year.)