“…our stories influence what we see and what we believe is possible or impossible in the world.” – Ethan Miller

My post last week was a response to events in Australian politics that I found exasperating. The political circus continued to get my goat so much I wrote a letter to The Age.  My week of political writing got me thinking about the role of fiction in relation to politics.

My week of political writing got me thinking about the role of fiction in relation to politics.

When we consider politics and writing we generally think of journalists. If a journalist fabricates content it is a betrayal of public trust, but making stuff up is the very purpose of creative fiction so does it have a role in politics? Is there such a thing as fiction that is not political? Is writing fiction a political act?

Many say they are not political (or not interested in politics), but the sociopolitical environment in which we reside shapes our entire lives. Politics determines the haves and have-nots. It tells us who’s experience is legitimate. For example governments determine whether  medical facilities exist to ensure we survive childbirth, dictates if we get the opportunity to learn to write at all, the price of milk, who we can and cannot love, and the type of death we can have. Our very existence is enmeshed in, and shaped by the political environment(s) we live in and are exposed to.

medical facilities exist to ensure we survive childbirth, dictates if we get the opportunity to learn to write at all, the price of milk, who we can and cannot love, and the type of death we can have. Our very existence is enmeshed in, and shaped by the political environment(s) we live in and are exposed to.

Work of the creative imagination, be it fiction, poetry, art or drama, is shaped by our own experience and our views of the world – in other words our own sociopolitical lens. The world shapes us, and then as writers we try to shape the world. We question or bend reality, invent new worlds and invite readers to consider a new perspective. To understand the other. We pick out themes and create personalities that we sew together into a plot to show, magnify or transform how a particular set of circumstances can impact on the world now, or in the future.

What reader would not be able to name a book that had a significant influence on their lives? Writers, story tellers and poets have been holding a mirror up to reality for centuries. They often say what would otherwise be considered unsay-able in public.

The threat writers pose is evident when we study the history of censured, banned or  burned books. Examples of fiction works that have been subject to some kind of censorship or ban at one time or another include Dr Seuss, Winnie the Pooh, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Catch-22, The Da Vinci Code, Doctor Zhivago, Nineteen Eighty-Four, The Satanic Verses, Sophie’s Choice, The Well of Loneliness and Ulysses. The more restrictive a political regime, the more likely it is to see text as a threat. Over 25,000 books were burnt in Munich four months into Hitler’s regime for being ‘unGerman’.

burned books. Examples of fiction works that have been subject to some kind of censorship or ban at one time or another include Dr Seuss, Winnie the Pooh, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Catch-22, The Da Vinci Code, Doctor Zhivago, Nineteen Eighty-Four, The Satanic Verses, Sophie’s Choice, The Well of Loneliness and Ulysses. The more restrictive a political regime, the more likely it is to see text as a threat. Over 25,000 books were burnt in Munich four months into Hitler’s regime for being ‘unGerman’.

A lesser known but poignant example of how literature can threaten and intersect with politics was a book called New Portuguese Letters (Novas Cartas Portuguesas) by Muria Isabel Barreno, Muria Teresa Horta and Maria Vento da Costa. The book, published in 1972, was a post-modern collage of fiction, personal letters, poetry, and erotica inspired by the original letters of a Portuguese nun, Mariana Alcoforado to her lover, the Chevalier de Chailly, at the time of Portugal’s struggle for independence against Spain. When New Portuguese Letters was written the Portuguese had been living under a dictatorship for almost fifty years and the book exposed the tyrannical relations that existed between the sexes.

The authorities banned New Portuguese Letters soon after its release – though not before a copy was smuggled to French feminists in Paris who arranged for its translation. The three Marias were arrested and allegedly tortured by the regimes secret police. They were charged with ‘abuse of the freedom of the press’ and ‘outrage to public decency’ by a censorship committee. The three women were criticized because they wrote like men. They were sexually explicit, frank about their desires, fantasies, sexuality and bodies. They critiqued patriarchal structures, family violence and political repression.

The trial dragged on for two years, made worldwide headlines and gave rise to protests  outside Portuguese embassies in Europe, the United States and Brazil. On 25 April 1974 a bloodless coup overthrew the regime. It was called the Carnation Revolution because red carnations were put in the ends of soldiers’ gun barrels. Soon after the coup the case against the three Marias was dismissed, the women freed and the book became a literary symbol of women’s liberation, erotic art, and the Portuguese revolution.

outside Portuguese embassies in Europe, the United States and Brazil. On 25 April 1974 a bloodless coup overthrew the regime. It was called the Carnation Revolution because red carnations were put in the ends of soldiers’ gun barrels. Soon after the coup the case against the three Marias was dismissed, the women freed and the book became a literary symbol of women’s liberation, erotic art, and the Portuguese revolution.

At its essence politics is about power and the rules we impose on society as a way of maintaining order. Do all authors strive to effect change in the world through their writing? If we don’t, why do we hope to be published and read?

What about genre fiction? Is romance gender politics at work? The genre is often dismissed as unworthy. Is that not itself political? Is to disregard romance a dismissal of women (the main consumers of romance), their views on relationships and their sexuality?

Is mystery fiction social justice at work? It often explores and gives voice to the fringes of society – drugs, prostitution, the dispossessed, or the underdog taking on the powerful elite. The very essence of a mystery is about who holds power, who abuses power and how the imbalance can be redressed. That is political. Mystery authors often use their writing to bring to light the concerns of minority groups and to provide commentary on a societies moral issues – Val McDermid’s lesbian protagonist, Lindsay Gordon; Emma Viskic’s deaf character, Caleb; Barry Maitland’s Aboriginal protagonist in the Belltree trilogy.

Reading a novel uncouples us from our ordinary lives and transports us to a self-created world through our interaction with a work of fiction. We read fiction to get ‘lost in a book’ or to ‘escape from our own existence’. Reading is an opportunity for some kind of small transformation.

Writing is a way to contribute to the development of a liberal and democratic society. We implant meaning and messages in our plots that we hope will influence how our readers think, not only entertain them.

Writing is a way to contribute to the development of a liberal and democratic society. We implant meaning and messages in our plots that we hope will influence how our readers think, not only entertain them.

We judge and unpack what we read and ascribe a value to books. That is political – just read any book review or go to a book club meeting and listen to the debate about a novel to see how a single story can take on different contours and unique significance for individual readers.

How do you hope to influence your readers?

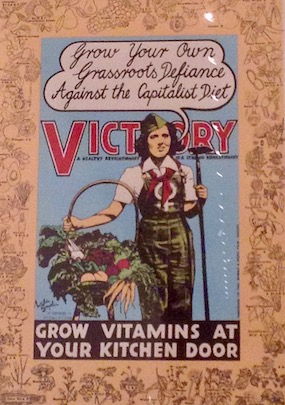

Main image: DOX Centre for Contemporary Art, Prague;

Inset images in order: Letter to The Age; Street Art, San Francisco; Guggenheim museum, New York City; Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane; Threat and Sanctuary, Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Hi Rachel, Thanks for coming over yesterday. I hope the journey home wasn’t too onerous. After you left I read your latest blog which I thought an excellent and thoughtful piece of work. Maybe there is a journalist or essayist inside you waiting to get out. More of the same, please. Love, Dad >

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

Love this post. As you noted politics influences everything. If I ever get around to writing I would like to influence people to treat others with compassion and respect. I never wanted to come to Bali because of how exploited the people are. Like any invaded country…ah I really want to respond in more depth but not on my phone. I will when we return home however

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

Thank you. I felt that conflict when I was working in development – its one of the reasons I left the industry. I found the power dynamics between the westerners ‘helping’ and the locals being ‘helped’ increasingly uncomfortable. I did a post conflict posting in Timor and the image of vultures to the carrion kept coming to mind. I realised it was time to change jobs…Didn’t realise you had gone to Bali. I hope you enjoy it despite the inner conflict. Tread lightly…

LikeLike